- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

This time last year, I was an elementary-school heartthrob.

As a substitute teacher, I went by Mr. C, or Mr. Cav, a name I’d scrawl on dry-erase boards every morning, sweeping back my hair as I explained to the class that, when it came to titles, I was easy.

“Whatever you’re comfortable with,” I’d tell them. And just like that, I was the young, cool teacher who broke all the rules.

One time, I gained a class’ respect by using the word “screw” in a lecture on long division. They all gasped, knowing full well who was in charge.

“That’s right,” I told them. “Better believe I’m a grown-up. I can stay up late and spoil my appetite whenever I want to. God only knows what I’m capable of.”

I’d scratch at the two day’s worth of stubble growing on my chin, a beard that let every sub-10-year-old there know that I was a different kind of teacher. The sort of hardened inner-city hero they’d seen in movies. The kind that starts after-school rap clubs and teaches gangsters to express themselves through dance, not violence.

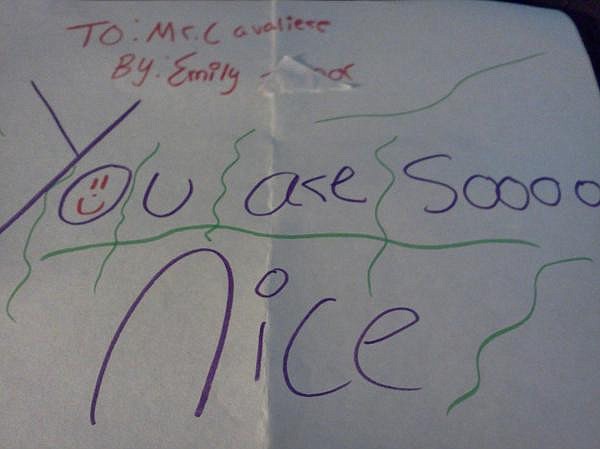

As Flagler’s resident “bad boy” sub, I’d attract entourages of little girls at recess, each one giving me handmade cards and saying things like, “You look like a fashion designer — in a good way!”

Fourth-grade honies would snap photos of me with their cell phones, using the shots at lunch to barter with friends for extra tater tots.

Like all women, it was my apathy which attracted them. They’d ask if they could get up to sharpen a pencil, and before even finishing their sentence I’d drop a, “Nnnope.”

They’d tell me I was the best sub they ever had, make me dragons out of loose-leaf and hug my leg, and I’d tell them plainly to get lost.

But just when I thought I had this whole “teaching” thing figured out, I’d blink, and the little twerps turn on me.

Youth was the only weapon I had against those squirts and whippersnappers, and every one of them knew it. Even if I had any real administrative pull, every pipsqueak in every class I ever worked knew I’d never have the heart to actually use it.

Sure, if somebody was picking on a classmate, that was one thing. But if they were picking on me, I was never quite able to turn on the adult switch and not smile at the innocent way they ate me alive.

They were like these tiny, cartoon versions of mobsters. Their defiance wasn’t personal; it was business. And seconds after they’d blatantly interrupt one of my lectures — the seven-year-old equivalent of breaking my thumbs — they’d compliment my shoes and ask, “Do you have hobbies? You look like the kinda guy who’d have hobbies.”

I once made a first-grader named Xander join the reading carpet as I narrated a book about pumpkins, and he immediately started balling. It was 10 minutes into my first ever first-grade group, and that’s when I knew I wasn’t cut out for the classroom.

Subbing was a temporary thing, something to do until I finally found that first real move-out-of-my-parents’ job and started understanding why I just spent all that money in college. During recess, I’d think about what I could possibly do with my life, where I could go, what I would be like as a real adult, with a real job, real money and real problems. My angst was worst in the winter months. I’ve always found something quiet and reflective in leafless trees and long sleeves.

Those days, the breeze would be cold but the sun would be warm, and I’d pace down a sidewalk as groups played football all around me. I’d sip coffee from a thermos, eat a few dark chocolate blocks and watch them juke and jump and cheer, not even knowing I was there.

No one was ever mean or crazy during recess. They played nice. They were cool, lost in the laughing chatter of the playground. They were finally doing what they’d been waiting to do all day. They were free. They were where they wanted to be.

I’d pace, and sip and swallow, trying to recapture that feeling. Then I’d throw a ball back into play when it was knocked toward me. And one of the kids would yell, “Thanks, Mr. C!” And I’d raise my mug to them.

For more from Mike Cavaliere’s blog, CLICK HERE.