- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

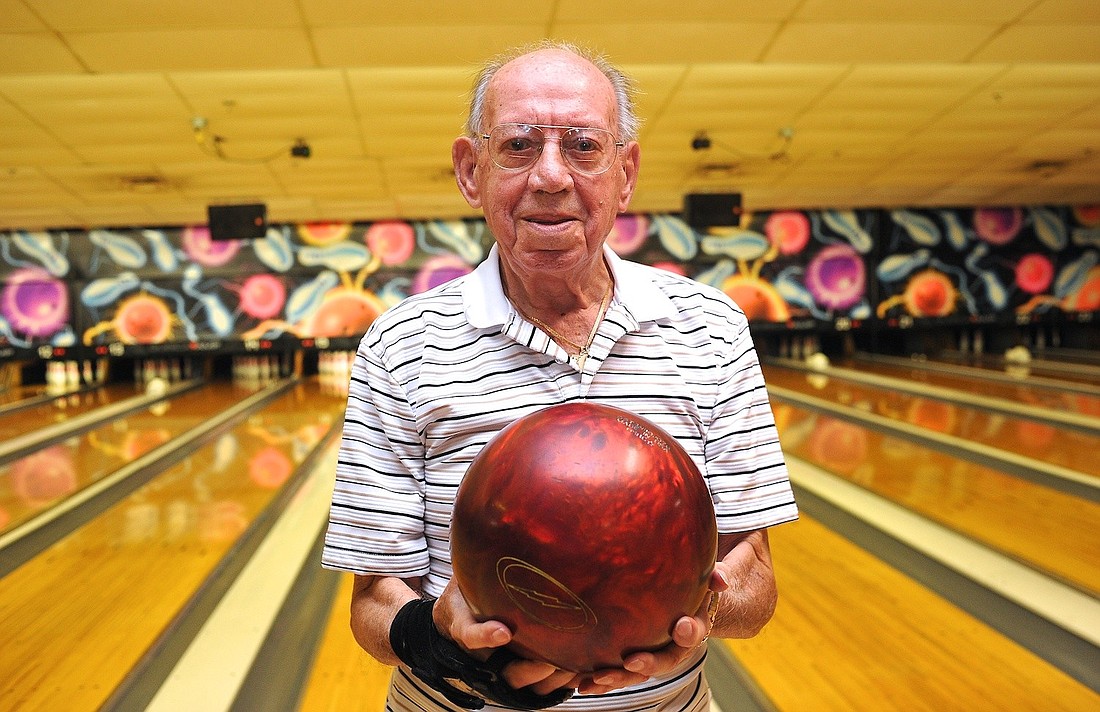

Charlie Truglia, 99, fastens a black wrist strap to his right hand. It’s dead at Palm Coast Lanes around 1 p.m. on a Tuesday, with just a few diehards flanking him and his friend Lou Culmone, 82, on nearby lanes.

After all these years, the game is still fresh, and it’s still connecting Truglia with memories and faces from the past. Truglia is fueled by “the people that love him,” Culmone said. “It’s remarkable what he does for a man of his age.”

Today, Truglia rolls in two Palm Coast leagues, and still travels cross-country for national tournaments.

Once the scoreboard is configured, Truglia fingers a dark red ball and readies for his first roll on lane No. 15.

“These first few balls,” Truglia says, “anything can happen.”

Beer garden variety

In 1930s New York, if you wanted to drive anything other than a car, you needed a chauffeur’s license. Born and raised in Long Island’s Oyster Bay, Truglia earned his license at 18 and secured a gig delivering ice from the back of a truck.

“At that time, I delivered ice to the beer gardens also,” he said. “There was one beer garden that had four lanes in the back.”

Beer gardens were small bars or pubs. Some featured a few tables, a dartboard and, occasionally, an abbreviated bowling alley. On one fateful delivery run, Truglia put down the ice and picked up a 16-pound ball. He joined a weekday league and became hooked. That first league snowballed into work leagues and countless tournaments across the Empire State.

“That’s the first time that I bowled, that I picked up a ball,” he said. “In those days, it was very cheap, like a quarter a game.”

He continued to deliver ice well into his 20s. Somewhere along the line, in 1934, he was invited to a wedding where his future wife, Josephine, was the maid of honor. The two hit it off and were married in 1935. The courtship wasn’t without its bumps, though. Josephine’s father requested to accompany the lovebirds on their first date, a prospect Charlie balked at.

“I’m thinking, ‘Is this guy serious?’” Truglia said.

Josephine

Today, photos of grandchildren and great-grandchildren have overtaken the walls of Truglia’s Palm Coast home. But he’s no longer able to admire them with his wife. After 76 years of marriage, Josephine Truglia died in November 2011.

Friends like Culmone and Sid Thorpe tried to keep their friend’s spirits up.

“I think he was really sad,” said Thorpe, a retired New York City transit worker who met Truglia in the 1990s. “When Jo got really sick, he had to slow down his bowling to take care of her. I think the bowling kind of opened up — now, he still missed his wife — but the bowling really picked up his spirits.”

Culmone took Truglia on a cruise, and the friends continued to go out to dinner each Sunday evening, a tradition started as a double date before Josephine’s death.

Thanks to another connection from his bowling past, Truglia also reunited with an old friend.

“One of my teammates — a good friend — shot a 300 game, and it was quite a thrill standing there, waiting for him to throw the last ball,” Truglia recalled. “He threw the last ball, he buried it, got a strike and he turned around. Then he ran, and he jumped on me.”

The friend, Clyde Gaylord, had a daughter named Laura, and Truglia baptized her, becoming her godfather.

That bond was never broken.Shortly after Josephine’s death, Laura Gaylord was living in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and she and Truglia kept in frequent phone contact. And so, after he drove 650-plus miles nonstop to a tournament in Baton Rouge, she followed him back to Palm Coast to help take care of him.

With that, the baby Truglia once held and promised to provide for in case of the unthinkable now lives with him, returning the favor.

Friends note Truglia is slowing down as he approaches the century mark. For example, he hasn’t mowed the lawn or been as avid of a handyman around the house much since his wife’s death.

But bowling is a constant for Truglia, as U.S. presidents, technologies and millennia expire around him.

“He loves the game, and I think it’s what keeps his spark going,” Culmone said. “If it wasn’t for bowling, I think he’d be gone now. I think the day he gives it up, he’s not going to live that long.”

A straight shooter

Despite a slow start that afternoon at Palm Coast Lanes, Truglia clears triple digits with a strike in the 10th frame. His scoring average hovered around 160 in league play this year, so this is going to be a bad score. But he’s got one more shot — two with another strike. His second roll is true, but when pins settle, he’s left with a 5-10 split.

He goes to his blue ball with the word “Zone,” written on it. It’s specifically designed to pick up spares.

His approach today consists of three measured steps. It always used to be five — before a January 2013 run-in with an unmarked curb while at a tournament in Ocala. Truglia suffered a cracked kneecap that has limited him ever since, but he still managed to bowl three games the day after the incident. And he hasn’t relinquished his grudge against the pavement. “No good,” he says. “It’s supposed to yellow. It was a curb.”

After three steps, he lets it fly. It’s a straight shot. Truglia never puts English on the ball; he keeps his wrist at 10 o’clock, as rigid as possible. The ball slides along the bone-dry surface, and he holds his pose. It’s a difficult shot, and it’s unlikely he’ll nick both pins. But that’s the beauty of bowling: Anything can happen.