- February 25, 2025

A lawyer who filed an August 2012 complaint against the Flagler Schools and four other districts in northern Florida over discrimination in the districts’ school systems told a packed house at the African American Cultural Society Tuesday night that glaring gaps in disciplinary and educational outcomes persist in Flagler County, despite some progress.

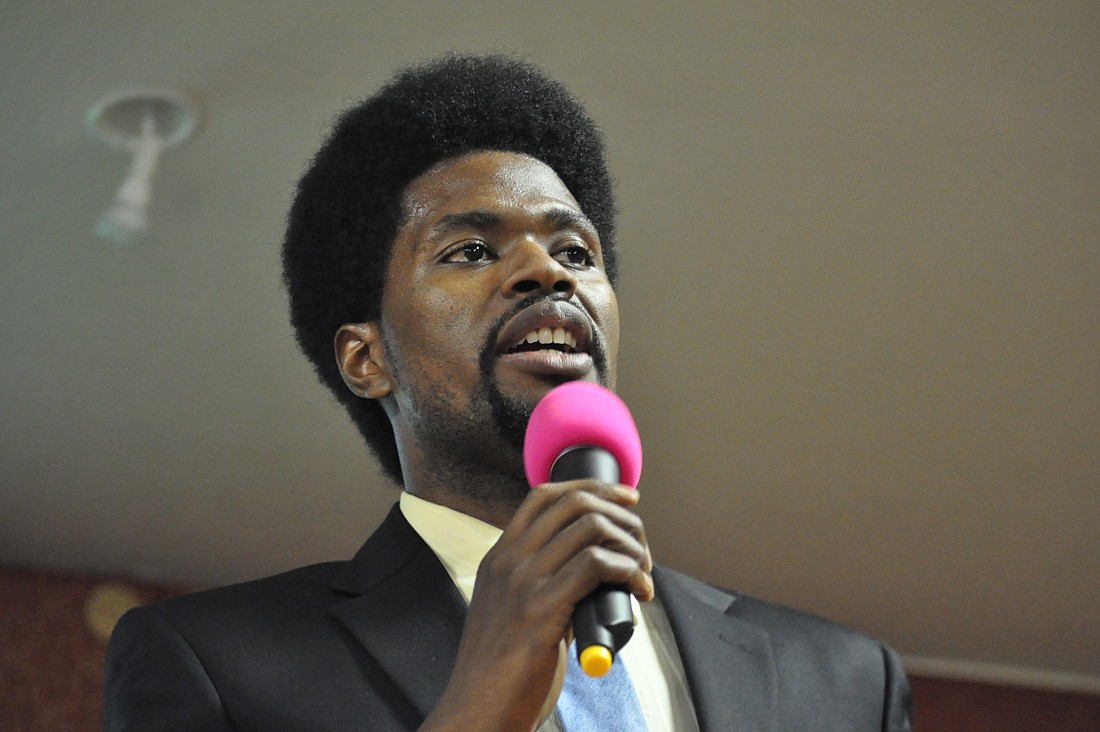

Amir Whitaker, an attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center, told about 130 attendees at the address during a regular meeting of the Flagler County NAACP that black students are 16% of the district’s student population, but accounted for 33% of suspensions in 2013 and 36% of suspensions in 2014.

They’re only 4% of the population in the district’s gifted classes, he said, and there is only one black male student in dual enrollment classes, while there are 52 white male students. (Those numbers could not be confirmed by the school district and might be outdated, according to Student Services Director Katrina Townsend.) The disparity persists despite general progress in the district’s handling of disciplinary matters, particularly reductions in overall numbers of suspensions from 1,821 in 2013 to 1,557 in 2014, he said. And only 6% of the district’s teachers — and 4% of elementary school teachers — are black.

“Flagler has made tremendous improvements,” he said. But the disparities, he said, are the result of “an inherited system. … If you look at student outcomes today, you still see two separate stories.”

“Discipline is not exercised equally on our students,” he said. “Blacks are 16% of students in Flagler, but 39% of students suspended multiple times.”

Flagler Schools Superintendent Jacob Oliva, who attended the NAACP meeting, said the district is working to fix the gap, but work remains. “Since we received the initial complaint, we’ve had a team of folks working hard on trying to come up with different solutions on how to meet our students’ needs,” Oliva said.

Townsend, who also attended the meeting, said in an interview Jan. 28 that although the percentage of black teachers in the district is low, 25% of the district’s principals are black, as are 18% of assistant principals. Of new educators hired in the 2013-2014 school year, she said, 19% — 21 teachers — are black.

The case docket of the Southern Poverty Law Center complaint against Flagler, Escambia, Bay, Okaloosa and Suwannee school districts said black students in each of those counties “were subjected to harsh disciplinary policies at a far higher rate than their white classmates” and “were often subjected to long-term suspensions, expulsions and even arrested at school for relatively minor misconduct.”

Whitaker spent much of the day before his Jan. 27 address touring Flagler County schools and meeting with district staff, including Oliva and Townsend. Of the five northern Florida county school districts whose SPLC civil rights complaints he helped file, he said, Flagler is the one that seems the most promising, “because of the people you have here.”

“I haven’t encountered anyone that I genuinely believe is just racist and wants to suspend black students more or wants to expel black students,” he said.

Instead, he said, the difference in educational outcomes and in disciplinary enforcement likely stems from implicit bias and from the history of segregation that led Flagler County to become one of the 16 of Florida’s 67 counties to remain under court jurisdiction, because its schools remained segregated into the 1970s.

Whitaker highlighted the kind of “implicit bias” that might lead to black people being treated in a discriminatory manner even by well-meaning white people by playing a brief clip from the ABC program, “What Would You Do,” in which three actors — one a young white man, one a young black man, and one a young white woman — went out in separate instances in a busy public park and began an obvious attempt to steal a bike by breaking its chain lock with a bolt cutter. The young black man was immediately set upon by hostile passersby, while the white man received little attention even when he told questioners that the bike wasn’t his. The white woman received offers to help.

Differences between the treatment of black and white students may be especially pronounced in southern school districts that long fought desegregation, but the problem is a national one: Data compiled in a brief on school discipline by the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights in March 2014 stated that, nationwide, “Black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students. On average, 5% of white students are suspended, compared to 16% of black students.”

And black children are more likely to be arrested in school and enter what has been called the “school to prison pipeline”: “While black students represent 16% of student enrollment, they represent 27% of students referred to law enforcement and 31% of students subjected to a school-related arrest,” according to the Office of Civil Rights brief.

Out-of-school suspensions and expulsions, Whitaker said, can lead to other problems: Students who are suspended fall behind in their coursework, are about twice as likely to drop out, and often spend their out of school time in places that aren’t as safe as school.

Trayvon Martin, Whitaker pointed out, went to Sanford — where he was shot by George Zimmerman — to stay with his father after he’d been suspended in his Miami-Dade County school.

“When you suspend someone, you reduce what is called the opportunity to learn. … You spend the rest of the year trying to catch up,” he said. “So we don’t need to send our children home. We need to find better alternatives.”

Flagler County has moved in that direction, as have at least two other school districts named in the SPLC complaint. See the box, “Other Districts Respond,” beneath this story, for more details.

In Flagler, Oliva said, “We have a district disciplinary review committee, and we have made revisions to our code of conduct and implemented an in-lieu program for students under disciplinary review to reduce the number of expulsions.” No district students have been expelled so far this school year, he said.

Oliva said the district has made minority hiring a focus. It has analyzed students’ pre-SAT data and arranged for meetings with kids who show the potential to succeed in accelerated learning programs — such as dual enrollment, International Baccalaureate, and Advanced Placement classes — to make sure minority students are aware of and can take advantage of such opportunities.

As for overall disciplinary policy, he said, “We don’t want to necessarily take a punitive approach to discipline, but a supportive approach. … Our data show we’re making great strides and gains, but we still have more work to do.”

But in a question and answer session at the end of the event, Lynnette Callender, a recent candidate for the Flagler County School Board, said the local black community has been too willing to put up with vague promises of improvement from the district, especially on the subject of minority hiring.

“When we’re told, gently, ‘Oh, we will look at getting, possibly, more teachers of color’ — that’s too vague. Let’s set a time limit for results. … We’ve been very sweet, kind and gentle,” she said. “Enough is enough.”

The NAACP also voted at the end of the event to examine and discuss the contracts signed between the district and school resource officers, the Sheriff’s Office deputies assigned to schools.

“School resource officers should be the resource for our children,” said Flagler NAACP President Linda Sharpe-Haywood, a former teacher and police officer. “That police officer is supposed to be the go-to person when that child feels endangered or when that child has a problem. They are not supposed to be the person who shoves them in a room, interrogates them and scares the bejesus out of them. … We should demand that they be trained to be resource officers, not an extension of the juvenile justice system.”

Townsend told meeting attendees that the district welcomes suggestions and feedback from the community and others interested in students’ success, including the SPLC. “It is a team effort between everyone that is interested in success for kids,” she said to the audience. “I offer you an open invitation to set an appointment and come into the schools ... to see the amazing things that the kids are doing.”

BOX: OTHER DISTRICTS RESPOND

The Escambia and Okaloosa County School districts were two of the five that were a subject of a 2012 Southern Poverty Law Center complaint about school discrimination. Here’s what officials from those counties say about what has changed.

Escambia County

“We were actually in process of implementing quite a few processes before they came in with their complaint,” Escambia County School District Superintendent Malcolm Thomas said, including an in-school suspension program that has reduced out-of-school suspensions from about 8,700 students in the 2006-2007 school year to about 2,750 students last year, and a positive behavior support program that rewards students for good behavior through a token system that lets them buy toys or other items from school stores.“They wanted to see you do all of your district, and do it immediately — that just wasn’t going to be effective for Escambia. For one, we didn’t have the resources,” he said. “We’re moving in the right direction, but there is still work to be accomplished.”

Okaloosa County

“We’ve done a lot of work to improve things,” Okaloosa County School District Safety, Health and Athletics Specialist Andy Johnson said. “Last year we implemented a program that we now call the Student Training Program. A student who in the past would have received an out-of-school suspension, now those students are assigned a day or two or three of student training.” That takes place in a small classroom where students do their regular coursework and work with a “trainer” to improve their behavior. The change has led to a “dramatic decrease in the number of out-of-school suspensions,” he said.