- December 15, 2025

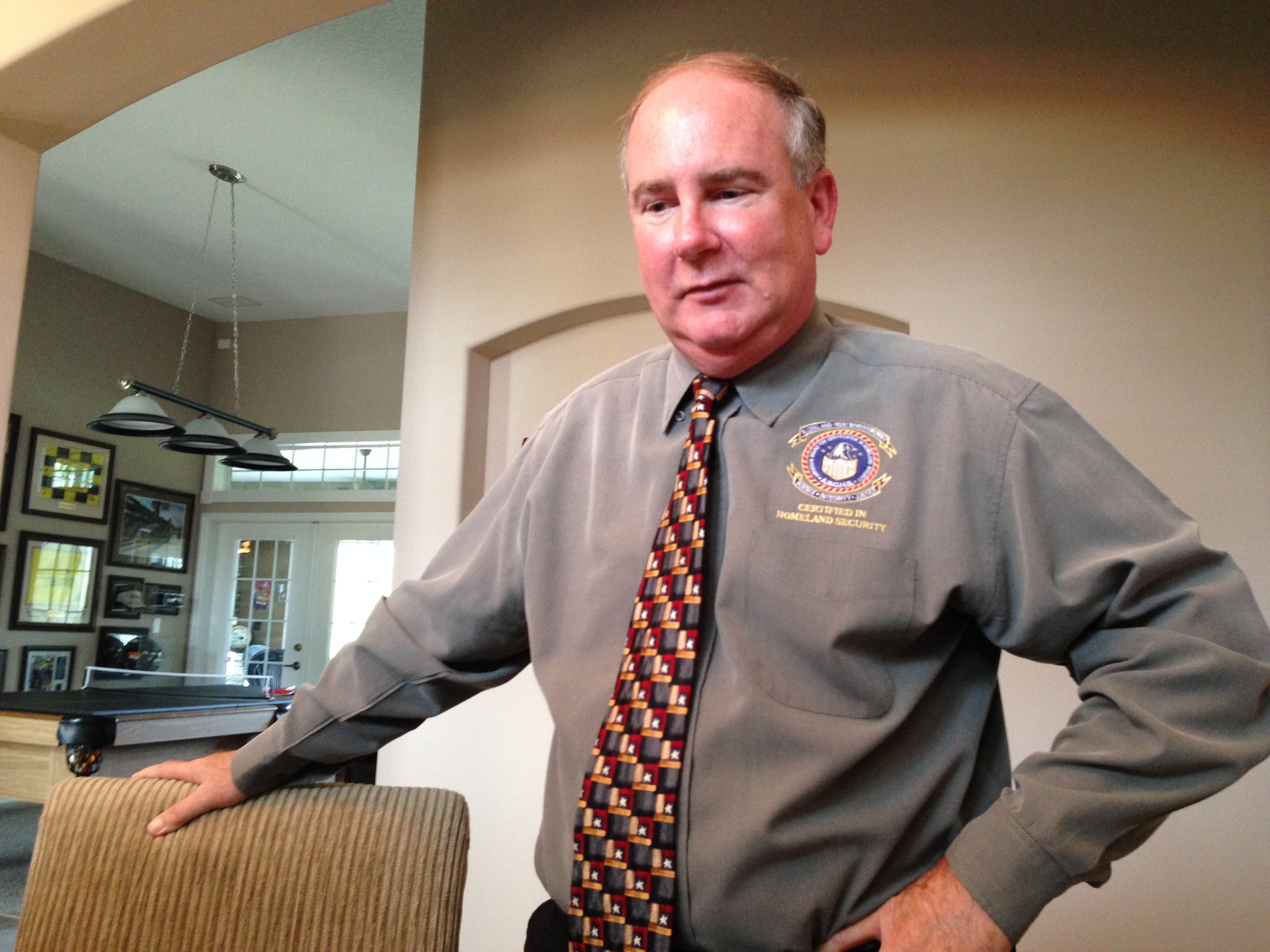

Rick Staly greeted me at the door of his Palm Coast Plantation home wearing a gray dress shirt with a fancy seal on the left breast with these words embroidered in gold: “Certified In Homeland Security.”

Staly, who retired as Flagler County undersheriff in April 2015 after a rocky relationship with Sheriff Jim Manfre, was previously a decorated deputy and undersheriff in Orange County. In between his work in Orange and Flagler, he was a successful businessman as the owner of a security company. In all, he has 40 years of law enforcement experience and has filed as a Republican in the 2016 sheriff’s race. I met with him Sept. 10 for an interview.

As he opened the door, a small dog raced out. Staly seemed amused by the dog’s unruliness. “Stitch, come on,” he said, “you’re fooling around.” Staly said to me, “She minds about as good as a cat.”

Staly is 59 years old, and his home is evidence of the great success he had in the sale of his security company. The home is spacious and filled with fine furniture and decorations. We sat at a long table in the formal dining room.

Staly is a man with a twinkle in his eye, a quick smile, a monotone voice and a graying combover. He also has a clear perspective on the sheriff’s race in 2016 — and any year, for that matter.

“This is one of the most important elections that a voter does,” he said. “Because we are talking about their direct safety and security in where they live and work and visit. So this is one of the most important positions that has a direct impact on your quality of life. Others also have direct impact, but this one talks about how safe is your house. You work hard for your stuff, and if your house gets burglarized, then you worked hard and someone else took it.”

Rick Staly was born in Jacksonville before moving to Winter Park.

A compassionate man without much education, his father was a Navy veteran and a carpenter. He owned Royal Cabinets (“Where quality is king and service is queen”) in Orlando, but cash flow problems eventually drove him to bankruptcy. Staly’s grandparents had to bring the family food to eat, and that is one reason why, as president of the Rotary Club in Flagler County, Staly encouraged the club members to bring to the meetings nonperishable food items to donate to food pantries.

The business failings put a strain on his parents’ marriage, and they divorced when Staly was 12.

Staly’s mother was well educated. She was a mental health social worker for a 40-year career, and that gave Staly some exposure to people with disabilities. When he became undersheriff in Flagler County years later, Staly said, he was attuned to the high number of incidents that used the Baker Act, which allows law enforcement officers to people who, as a result of mental illness, are a danger to themselves or others.

Now in Flagler County, he said, “we have a triage assessment center that we were able, in a collaborative effort, to create a Baker Act initial screen facility. It saves time for the deputies. I was really surprised at how many baker acts we were getting here.”

At 58 years old, Staly’s father had a massive stroke that paralyzed his right side and made him unable to talk. Staly took him fishing one time by lifting him and his wheelchair into the boat. His father died in December 2014, at the age of 84.

His mother is still alive today, at 94, and Staly said he takes her grocery shopping when he visits her.

“Mother tells a story that I used to ride my bicycle around and pull over other neighborhood kids,” Staly recalled with a laugh. “I don’t remember that part, but I do remember riding my bicycle around, and I drew out a mike and a radio out of cardboard. I was watching ‘Dragnet,’ ‘Adam 12.’”

While working at a gas station during his high school years, Staly met a sheriff’s deputy and learned about the youth deputy program. He would ride around with deputies and observe them making arrests.

“Sometimes that caused me grief,” he said. “They would make arrests of people who went to school. I remember eating my lunch and a kid came up who had been arrested, and he had crunched up a bunch of crackers in a lunch bag, and he threw it down, and said, ‘Now arrest me for that.’ … I wouldn’t say I was probably the most popular kid in high school, but I was focused on where I was going to go.”

He graduated high school in 1974 and was hired as a police officer in Oviedo in 1975. Concerned that he wouldn’t be taken seriously when he pulled people over, he grew a mustache to make himself look older.

From Oviedo, he moved on to Altamonte Springs and then, in 1977, he became a deputy at Orange County. Meanwhile, he worked on his education and earned his bachelor’s degree in 1980.

A defining moment in his law enforcement career, and something for which he was given a Medal of Heroism by Gov. Rick Scott in 2015, occurred in 1978, when he was a corporal at Orange County.

He and a deputy, Ed Sarver, were called to respond to a threat at a gas station, but the suspect was gone. About 3/4 of a mile away, they found him at a fruit market, “raising all kind of cain.”

“Calm down or you’re going to jail,” Staly recalled telling the man.

The suspect responded that if Staly tried to arrest him, there would be a “tussle.”

“I told him he was wrong,” Staly told me. “But at the end of the day, he was right.”

The suspect threw grape soda at Staly, splashing it on his shoes and pants, and then ran. The next 11 seconds put Staly in a position to safe Deputy Sarver’s life, at risk of losing his own.

“We started chasing him,” Staly recalled. “Sarver ran. I got on the radio. I said, ‘We’re on foot pursuit.’ Sarver tackles him, and I’m still running up. I’m about where you’re sitting — that distance away. We’re in the parking lot of Elmer’s Paint and Body Shop. I saw Sarver on the bottom, and the suspect on top, and Sarver pushed him off.

“I’m running to them, and I saw Sarver pushing him back, and he had Sarver’s gun. … My plan was to draw my gun, spin around and run backwards for cover to this van. I knew I had to get his attention.

I don’t know the order of the rounds that hit me, I just know that I took two rounds in my gun arm, and one in my chest.

“I kicked him in the chest. I was still in the process of getting my gun out, and he fired first. I don’t know the order of the rounds that hit me, I just know that I took two rounds in my gun arm, and one in my chest. …

“At that same point, another deputy that had heard the foot pursuit was pulling in, and witnessed the entire shooting, and I was laying on the ground, and the suspect came running up, and the gun was pointing down at me, and I remember thinking, ‘I always wondered how I was going to die. Now I know.’

“The deputy was reaching for his shot gun, and the suspect shot through his windshield, and he got out and started returning fire with the suspect. The suspect was hit five times.

“He was doped up on Purple Haze, LSD derivative. … My understanding was that on the way to the hospital, he didn’t compain about the bullets.”

Staly saw the blood on his own body, and noted that the bullet holes in his arm were only flesh wounds, not life-threatening. But, he said, “I had a lot of pain in my chest. I kept saying, ‘Did it work? Did my vest work?’

“I had a bloody bruise, but there was no hole in me,” he said. “If the vest had not stopped it, you and I would not be talking to you right now. It would have tore through the chest cavity.”

Next call: “Man with a gun at Hotel Royal Plaza”

As if that weren’t intense enough, after his 30-day leave following the incident, his first call back on the job was on the midnight shift in the area of Disney World: “Man with a gun at Hotel Royal Plaza.”

The first shooting replayed itself in his mind as he drove to the hotel. Fortunately, in that incident, Staly was able to take the gun and arrest the suspect. “It was a great way to get back on that horse, but it was certainly a terrifying run down the interstate,” he said.

Another incident, about two months after he became a sergeant, put him in a position to make the decision whether to use tear gas in a building to flush out some suspects.

Why does these stories matter as you’re running for sheriff? I asked.

“It shows to the employees and the community that I’m a cop’s cop,” Staly said. “I’m great administrator, but I’ve also lived the shoes. I’ve provided the service. I’ve been the victim of a crime — that shooting. I’ve been the victim of a property crime. I’m empathetic with victims. I’ve been there.”

It struck me that this could be a significant issue in the 2016 campaign. According to a recent News-Journal story, Sheriff Jim Manfre is the only one of 67 sheriffs in the state who is not a former law enforcement officer. Manfre’s response to the question was that he has been elected twice on his credentials. Does the public care whether the sheriff has ever been a cop?

In Staly’s point of view, it matters to the deputies.

“The agency does not support the incumbent sheriff,” he said. “They want a leader that has come from the ranks that has been in their shoes, if you will. He will never be accepted by the agency. And he knows that because he’s told me that: ‘I know that I’m not accepted.’ He’s not accepted by his peers across the state, either. I can tell you that the sheriffs in this state, I know, they know me, and he’s not accepted by his peers.

"What I believe the employees want, is they want someone who has been there, who will back them, who will not play politics."

— Rick Staly

“So, without a doubt,” Staly continued, “what I believe the employees want, is they want someone who has been there, who will back them, who will not play politics, and they want this to be more than just a paycheck to them. I think I’ve proven that. I was undersheriff in Orange County and Flagler County. I went out on patrol, I make arrests, I’ve helped them serve arrest warrants and search warrants.”

He said he spent his Friday nights on patrol, as undersheriff (See a video here). That way, he said, “I don’t make decisions in a vacuum or in an ivory tower. And it’s good for me because it gets back to where I started out, serving the community and policing. It’s kind of a stress release day for me.”

I noted, also, that of all the candidates I have spoken with so far, Staly seemed to have the most vivid memories and compelling stories from his days on the street.

Staly also emphasized his training. I assume he wore his “Homeland Security” shirt for our interview on purpose, and he said he is the only candidate who is certified in Homeland Security.

He said he is also the only candidate who has graduated from the FBI National Academy. “That’s very prestigious,” he said. “Only 1% of law enforcement ever gets invited. It’s like the West Point of law enforcement.”

When Staly became undersheriff in Orange County, he determined that some of the sheriff’s decisions were “inappropriate.” He said, “I voiced my opinion, and he didn’t like that so much. And he eliminated my position as undersheriff. So I became a division chief of training.”

Later, Staly ran against the sheriff, Kevin Beary, in 2004.

“I knew I couldn’t beat him as a Republican,” Staly said. “I swallowed a very sour pill and changed parties and ran as a Democrat.”

Staly lost the election. Then, in January 2005, he filed ethics complaints against Berry, and eventually Berry pleaded guilty to four of them.

After Orange County, Staly began working in security for the Ginn Development Company in Flagler County. As the economy suffered, he could see that he was about to be laid off.

So, Staly and his wife, Debbie, whom he married in 2003, decided to combine their money and start their own security company, called American Eagle Sentry.

Three homeowners associations signed on right away, based on their past experience with Staly under Ginn.

“We started with 60 employees and a million in revenue,” he said. “In four years, it was 128 employees and $3.5 million. We had clients in Tampa, Orlando, Palm Coast, St. Augustine.”

The Stalys decided to sell the company in 2011, mostly because of the impact that Obamacare would have on the bottom line. “Fortunately,” he said, “we found a buyer that was willing to pay a premium dollar.”

This is one area that also stood out to me about Staly during our interview: He is the one candidate with a strong business track record, outside of his experience with budgets as a sheriff’s office administrator.

Staly agreed to be Jim Manfre’s undersheriff to begin Manfre’s term in 2012. But he disagreed with the way Manfre treated people, he said. I did not talk to Manfre about this; I’ll be interviewing him later for a profile of his own. Manfre has officially declared that he’s running for re-election. I imagine there are two sides to this story, but for now, I am presenting Staly's side.

“I stayed for the employees,” Staly said. “That’s the only reason I didn’t go after nine months. I was the buffer between him and the employees. The final straw was how he treated a particular employee during a personal crisis.”

According to Staly, their relationship was not broken at the time he retired. In fact, according to Staly, Manfre even encouraged him to run to be sheriff. Staly left for a cross-country vacation and said he was going to think about what to do next.

When Staly returned from his vacation, Manfre was upset, Staly recalled, because the documents from the state ethics investigators had been released.

Staly on Manfre: "If he listened to my advice, he wouldn’t be in half the trouble he was in."

“He wasn’t very happy,” Staly said. “I told the truth, and he fired a shot at me saying I gave him bad advice. Well, if he listened to my advice, he wouldn’t be in half the trouble he was in.”

Manfre’s approach to place blame on Staly — in Staly’s mind, “he threw me under the bus” — was the last straw. He recalled thinking, “He’ll read my decision about running for sheriff in the paper.”