- December 15, 2025

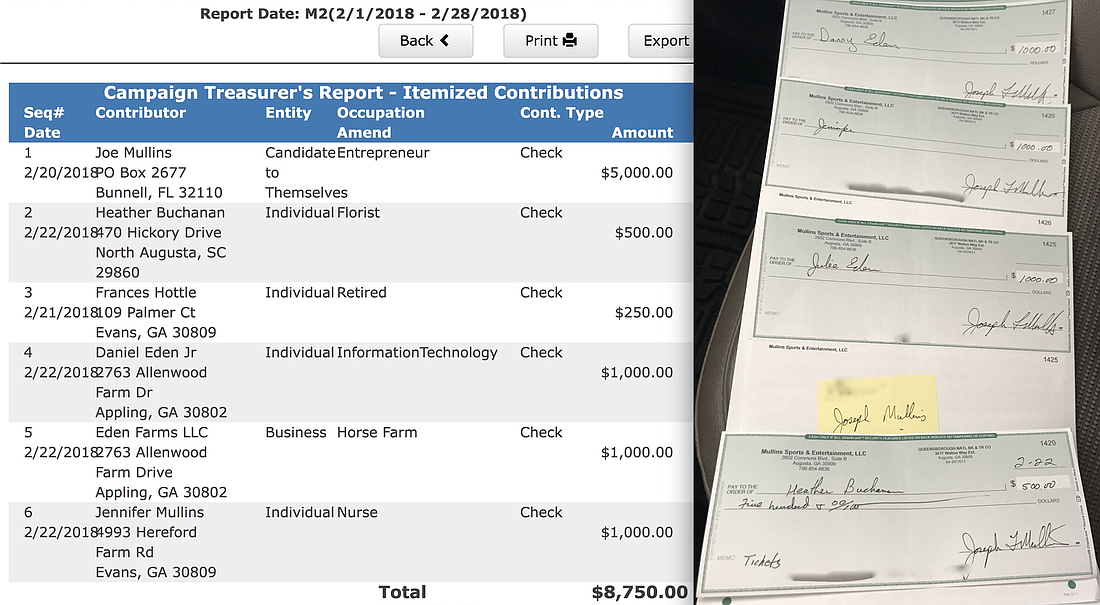

Flagler County Commission District 4 candidate Joe Mullins asked family members and one of his employees to donate to his campaign in exchange for immediately reimbursing them for an amount identical to their donation, according to a former Mullins employee. The employee, 47-year-old Heather Buchanan, provided the Palm Coast Observer with a photograph of checks from Mullins’ business account to people who are listed as campaign donors, including herself, in amounts that equal the reported donations.

If true, Mullins’ actions could be a violation of Florida’a campaign finance laws: It is illegal to donate to a political campaign under someone else’s name. Mullins denies the allegation.

Buchanan, a South Carolina resident who quit working for Mullins after speaking to the press about the campaign donations, said Mullins directed her to write a $500 from her personal account to his campaign and immediately reimbursed her with a $500 check from one of his business accounts.

“It was in my first few days of working there, and he was like, ‘Heather, you got a checking account?’” she said. “I said, ‘Yeah, I got two, why?’ He said, ‘Because I need you to write me a check,’ ‘For?’ And he says, ‘Well I’m going to turn around and give you one right back,’ and he doesn’t really answer me. And then as I was writing, he said, ‘Write it to ‘Joe Mullins campaign.’’ I said, ‘OK,’ and he said, ‘For $500.’”

She was uneasy about writing that check, because of ethical concerns and financial ones — Mullins was paying her $12 per hour, and she didn’t have much money in her account, she said. But she did it.

“I said, ‘Joe, don’t you make me bounce a check,’ and he’s like, ‘I’m giving you a check right back, you can take it to the bank immediately.’”

That was Feb. 22 — the date on which the Flagler County Supervisor of Elections website, which publishes candidates’ reports of their donations, shows a $500 donation from Buchanan to Mullins. The information submitted by the Mullins campaign to the Supervisor of Elections website also lists Buchanan as a florist, although she was not a florist when she made the donation: She’d stopped working as a florist to work for Mullins, she said.

Buchanan deposited Mullins’ $500 check to her shortly after receiving it. She later sent the Palm Coast Observer a photograph of the deposited check from her account made out to Mullins’ campaign.

After Buchanan wrote Mullins a check and he gave her one back, Mullins asked her to take three checks, each made out for $1,000 and signed by Mullins, to his two sisters, his brother-in-law and a family-owned business. Her instructions were to give them the checks in return for getting one from them to his campaign in the same amount, she said.

She was concerned that the reimbursement might be illegal, so she pulled over at gas station on the way, laid the four reimbursement checks from Mullins’ business account out on the passenger seat of her car, and took a photo of them. Then she delivered the checks and got checks back from the family members.

The allegedly reimbursed donations make up all but one of Mullins’ officially reported campaign donations so far — all reported for the month of February — other than a donation from himself to his own campaign.

The reimbursement of the campaign donation checks was first reported by Augusta, Georgia-based radio show host Austin Rhodes, who covered Mullins’ 2015 run for a Georgia statehouse seat and recognized the names of some of the donors.

The two men have an adversarial history: During the 2015 campaign, Rhodes had a restraining order upheld against Mullins. Mullins said he is suing Rhodes for defamation.

After the allegations that Mullins had reimbursed his campaign donors was made public through Rhodes’ reporting, Kimble Medley — a Flagler County resident and supporter of Nate McLaughlin, Mullins’ opponent in the District 4 race — contacted Gary Holland, assistant general counsel to the Florida Department of State, and asked how to file a complaint about Mullins’ reimbursement of his donors.

“The contributions may be contributions given in the name of another in violation of s. 106.08(5), FS,” Holland wrote in his reply. “If these offenses occurred, they are not only subject to civil penalties imposed by the Florida Elections Commission, but may be criminal violations in violation of s. 106.08(7), which would be under the jurisdiction of the applicable State Attorney.”

Holland also noted another issue: Mullins’ donation to himself appeared to have been made from his business account, and, if so, would exceed campaign finance limits.

“It appears that Mr. Mullins wrote a $5000 from his Georgia-based LLC – the contribution is from the LLC, not him personally, so it may be an excessive contribution in violation of s. 106.08(1), FS,” Holland wrote.

Mullins’ campaign statement also denied that allegation:

“Mr. Mullins’ initial $5,000 contribution to his campaign was made from his personal funds,” the statement wrote. “All such activities are permissible under Florida campaign finance laws. We have no interest in anyone supporting a campaign that they do not want to be a part of and will issue any refunds from the campaign to those persons.”