- November 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

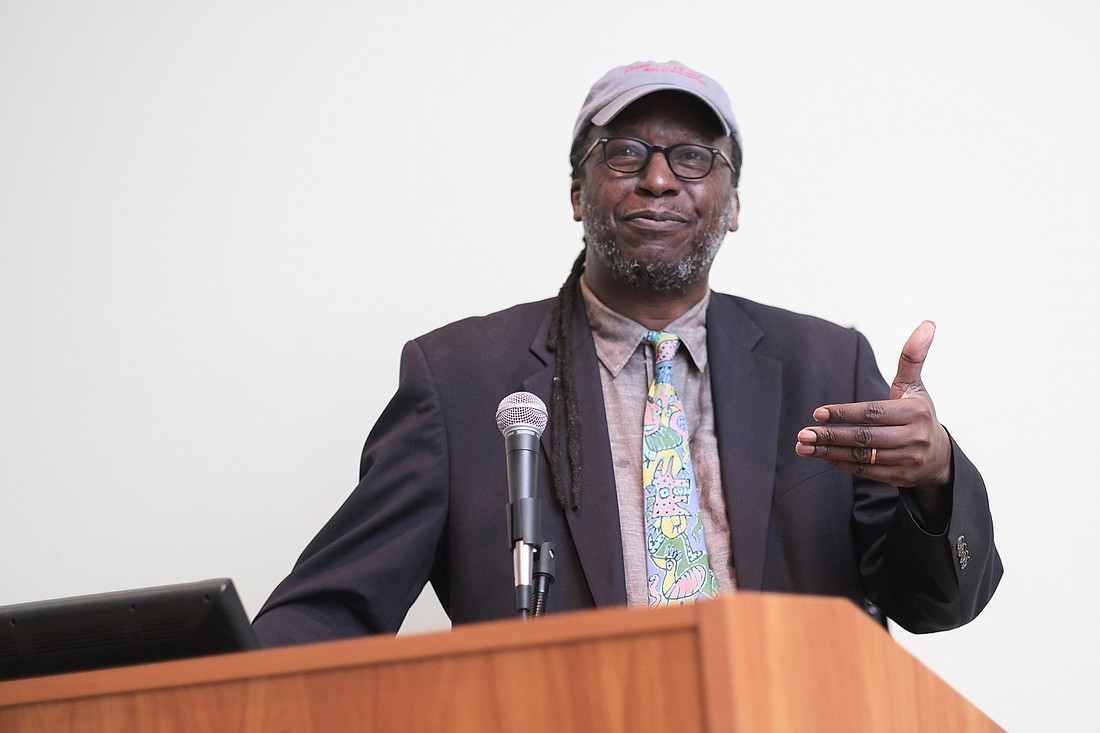

Cornelius Eady co-wrote “Running Man,” which was a finalist for the 1999 Pulitzer Prize in drama, and he is coming to Ormond Beach. He’ll be the featured speaker July 2, at the Ormond Memorial Art Museum, 78 E. Granada Blvd., sponsored by David Axelrod's Creative Happiness Institute.

Doors open at 5 p.m., and the program is from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 2. The event is free and open to the public, but registration is suggested because seating is limited. Visit shorturl.at/eiZ01 or email [email protected].

Eady, a professor in the MFA program at SUNY Stony Brook Southampton, also wrote “Brutal Imagination,” which won Newsday’s Oppenheimer award in 2002. He spoke with the Ormond Beach Observer on June 21.

Q: What influence can poets have in society today?

A: Poets don’t regulate laws, but we do have an influence in the way we want to live our lives. And I think without poetry, you have a very flat and uninteresting culture. So I think that most poets would feel that they’re on the side of progress and really want to see that working on various levels.

Q: What do you say to someone who feels poetry is unapproachable and hard to understand?

A: They’re reading the wrong poets. If they don’t feel that the poetry they are assigned to read is actually speaking to them or addressing the world that they live in, that’s unfortunate. But there’s lots of poets out there — Tim Seibles, Patricia Smith, Mahogany Browne — a whole slew of poets that use common vernacular that talk about the neighborhoods they come from, that don’t want you to feel that they separate themselves from the reader. I would encourage those readers to have a little bit of an adventure in a bookstore and see if they can find a book or a writer that really talks to them, because they’re out there. There isn’t a moratorium on accessibility in American poetry. I feel that my work is accessible. I’m an African American that comes form the inner city of Rochester, New York, a working class neighborhood. At the Ormond Beach reading, you’re going to find poems about my family, about music, about the political situation we’re in right now. But hopefully, not in a way that makes people feel they’re excluded excluded.

Q: What inspired your 1997 poem, “The Cab Driver Who Ripped Me Off,” a dramatic monologue told from the perspective of a cranky cab driver?

A: That’s a true story. With only a little bit of tweaking, that’s pretty much verbatim what he was telling me as he was driving me in the wrong direction to my house.

But they’re not all autobiographical. The poetry cycle for “Brutal Imagination,” where I personify the fictional suspect that Susan Smith invented to take the blame for the disappearance and murder of her two kids — that, of course, never happened to me.

Q: In your poem, “Charlie Chaplin Impersonates a Poet,” you have this great list of images — “doves, incandescent bulbs,/ Plastic roses.” — that are coming out of the poet’s mouth while visiting a university to give a reading. How do you know that one thing fits a list like that, while something else doesn’t?

A: It’s easy. You put it in the list, and you look at it, and if it doesn’t feel right, you take it out. I’m pretty sure I wanted to have something that would have the energy of slapstick but also surprise you, the way Chaplin’s pantomime surprised you at times. For example, he would turn two dinner rolls and two forks into a dance. I was hoping I would give a list that would approximate that kind of invention, but also something that violates protocol. In “Little Tramp,” he truly violates protocol time and time again, so I was trying to get that energy onto the page.

Q: Have you had good experiences being a visiting poet at universities or other events, like the one in Ormond Beach in July? What bad experiences have you had?

A: This is my second time; I was down there a few years ago and had a great time, pleased I’m begin invite back for a second visit.

The thought behind the Chaplin poem was the idea that sometimes poets find themselves in a place where they don’t quite fit what the protocol might be, or the anticipation or the assumptions of what the poet is supposed to be.

Q: Your poems often have an inviting, conversational tone, rather than a stuffy, academic one. Why is voice important in your work?

A: Voice in a poem is essential, regardless of who’s writing it. It’s the conveyor of the image, the lyric, the idea.

There’s an initial handshake, between the reader and the page; there’s a little negotiation there, whether you’re going to believe the tone of the speaker’s voice and let the speaker take you somewhere. Or, you’re going to say, “I don’t think the speaker knows what he’s talking about. I don’t believe the authority.”

The example I use is about the corpse come back from the dead, in Emily dickinson’s poem, “I Heard a Fly Buzz.” Nobody ever questions the impossibility of the first line, “I heard a Fly buzz — when I died.” It means that I came back as a corpse and wrote this poem. Nobody every goes, “That can’t happen.” You simple go with the authority of the voice. You’re going to follow that poet wherever the poem is going to lead you.

Some audiences are drawn to a more plainspoken, open kind of speech, and some are drawn to more of an academic stance. The difference between William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound, for example. Both Pound and William Carlos Williams were classmates at the University of Pennsylvania, and you see where Williams goes and where Pound goes. Pound was very comfortable presenting himself as a classicist, that the reader was obligated to look things up if they had to look things up.

For Williams, it has to be grounded in the real world. It isn’t trying to elevate itself away from what he considers to be the ideal reader. That is “the stance.” It’s not right or wrong, but at some point, the reader is developing their own voice, and they make an unconscious decision about which side of the line they’re going to fall on.

Q: One of my favorite poems of yours is “The Empty Dance Shoes,” in which the narrator says: “A practical and personal application of inertia/ Can be found in the question:/ Whose Turn Is It/ To Take Out The Garbage?” Have you ever asked this question in real life?

A: (Laughs) That’s a relationship question: Who’s going to take out the garbage, who’s going to answer the phone. You’re closest to the phone — no, you’re closest to the phone!

Q: In the same poem, you write about a 98-pound weakling who has been beat up and then is inspired by an ad in a comic book. What do you think and feel about that weakling?

That was a reference to the old Charles Atlas bodybuilding ads that used to be in comic books, where the scrawny kid who is trying to impress his dream girl at the beach, and the big man on campus kicks sand in the weakling’s face, and the weakling realizes he’s got to do something about that.

Most of us are 98-pound weaklings, which is why those ads were so popular.