- February 18, 2025

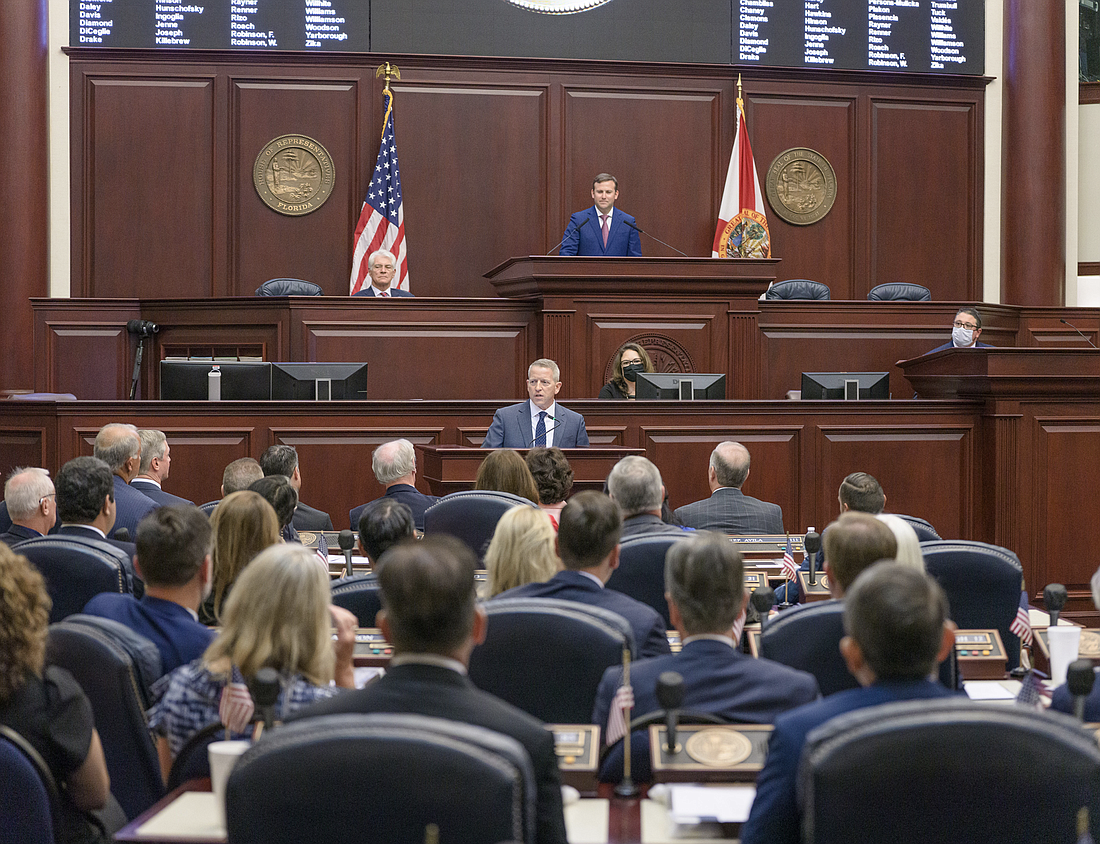

For Paul Renner to become speaker of the Florida House of Representatives and preside over the largest number of Republicans the state has ever elected, he had to be re-elected to his own fourth term by the citizens of Flagler and St. Johns counties on Nov. 8, and he was. But as far as his fellow members of the House are concerned, the matter was settled behind the closed doors of a conference room at a hotel in Orlando five years earlier, on June 30, 2017, after he had been elected by voters just once.

Between his first day on the floor, which was April 8, 2015, following his win in the special election in Palm Coast, and that day in 2017 in Orlando, Renner won an epic battle with a popular, sitting governor in his own party; he also fended off the campaign of a well-connected rival who also wanted to become speaker. Then, Renner turned that rival into a close ally, unifying the party.

This is the story of how he did it, based on my interviews with key House leaders who revealed their first impressions of Renner and how he rose to the occasion in his first two years.

House members can serve up to four two-year terms and are identified by their class; for example, if you are elected in 2016, you are part of the Class of 2016. One member of the Class of 2016 is chosen by classmates early on to become the speaker in the fourth term, in 2022-2024.

The member selected as future speaker is included in the leadership teams of the intermediate speakers, so he or she can gain experience needed when it is time to become speaker.

A speaker makes crucial decisions, but often not about the laws themselves. Instead, the speaker decides which members of the party will help work out the details of those bills.

About 2,000 bills are proposed each year. Each year, the speaker selects two or three dozen committee chairpersons, and the chairpersons decide which of those 2,000 bills their committees will consider. If a chairperson doesn’t think a proposed bill has a real chance of becoming a law, he or she could reject it before it even has a chance to be heard in the committee.

Most bills have to go through questioning by and gain approval of two to four committees before they have a chance to be debated further on the floor by the rest of the House members. If the bill wins support of the majority of the House, and if an identical bill has been coordinated to be passed in the Senate, the bill goes to the desk of the governor to be signed into law.

About 200, or 10%, of the bills that are initially proposed, are ultimately sent to the governor each year.

The power of the speaker lies in helping to set the agenda for the party and who is given power to lead the committees.

Renner won his primary and special election in 2015 in Palm Coast after having lost his first attempt by just two votes in 2014, in Jacksonville. Even while he was running in Jacksonville, he met some of the heavyweights in the House, in Tallahassee, including Richard Corcoran, who was speaker designate for 2016-2018 (meaning Corcoran would soon be the speaker of the House, the 100th in the state’s history).

“He showed courage as a freshman, carrying a bill that was not popular with the executive branch. He showed his mettle.”

—RAY RODRIGUES, House member

Corcoran remembers his first impression of Renner: “He was a military guy. I always tell people if they haven’t met Paul, he’s just a super honorable Eagle Scout kind of guy. His word’s his word. He knows what he believes. Great foundations. Always seeking to come up with a big vision. And it was just all very transparent the first time you met him.”

Renner was also visited by some candidates who hadn’t even been elected yet. Why did they care to meet him? Because while the voters were focused on who would represent them in the House, some candidates were already thinking ahead to 2020; they wanted to be speaker.

A would-be speaker had a tall task: Persuade the two dozen or so Republican candidates in other races across the state that you will be the best speaker — while you’re still a candidate yourself. Get enough of them to sign a pledge card to support you, and you will be declared the speaker.

But that system was viewed with skepticism by many. Corcoran compared it to the “wild, wild west.”

First of all, the speaker campaign is a big distraction from the task of actually winning the general election. Second, it leads to rivalries and divisions among the party.

The system left a bitter taste in Renner’s mouth. The speaker candidates are in a position, he recalled, “to play psychological games with people, to suggest that if [fellow candidates] don’t get on board with their team, that they’re going to be left behind, and that may have consequences, where they won’t have a meaningful time during their service, and that is exactly the opposite of what you want in somebody to lead the chamber. … Nobody wants somebody who’s a bully to have that kind of authority.”

In other words, if you pledge your support and your favorite doesn’t become speaker, the person who is elected speaker could shut you out from committee leadership positions in your future years in the House.

The 2014 race to become speaker designate ended particularly early: “right around the primaries,” according to Corcoran. “So none of those folks who were making commitments ever saw them legislate, ever saw them debate, saw them in committee, saw them in tough votes, saw them stand up to special interests, or any of that kind of stuff that you would hopefully want to see before you decide, ‘I’m going to make that guy, or girl, my leader.’”

Chris Sprowls won his election in 2014, in Pinellas County, and had campaigned to be speaker, but lost. In the coming weeks and months, however, the speaker designate lost the support of many members of his party, and some of the freshman House members in 2014 changed their minds and supported Sprowls. Ultimately, Sprowls became speaker.

The strife was considered so costly to the party that Corcoran and his leadership team, which now included the 2020-2022 Speaker Designate Sprowls, decided to change the rules. From now on, starting with the Class of 2016, no one could request anyone’s support to become speaker until after the first of the two sessions ended in that freshman class’s term. That would give speaker candidates a chance to show what they’re made of, finish the first session in March, and then they could have an organizational meeting on June 30, 2017, and elect the speaker designate for the 2022-2024 term.

By the time that change had been written into the Republican rules for the state, a lot had happened in Renner’s life. He had lost in 2014 but had moved to Palm Coast and won in 2015, meaning he was not a member of the Class of 2014, but instead a redshirt freshman member of the Class of 2016.

Under the old rules, Renner would have had an advantage in the race to become speaker because he had already been a member of the House for more than a year by the time of the 2016 primaries. That meant that while most of the Republicans who were interested in becoming speaker were still campaigning to be elected to the House, he was able to support their campaigns, help them fundraise, help them knock doors and show that he would be someone worthy of their support to be speaker. He also would have a year of experience actually legislating.

The rule change meant that Renner’s pledge cards had to be torn up.

Renner recalled telling his supporters, “You signed this for me, but you’re going to have to decide when the time comes whether you want to stick with me or not. I can’t talk to you about it until June 30.”

Still, Renner recalls that the change came as something of a relief.

“Even though they totally changed the rules of the game for me midstream, I was very supportive of it, and I remain, to this day, extremely supportive of it,” he said. “When you see people under stress politically, when you see them in a fight, then and only then can you say, ‘This person has the integrity, the humility, the principle and the courage to lead a very diverse group of people in a very important state at a very important time in history for our country.’”

Among Renner’s rivals was James Grant, already a star of the House.

The son of former Florida legislator John Grant, James Grant was young when he was first elected in 2010 to the House (he was born in 1982 and graduated from Stetson College of Law in 2009).

After a seven-month break in his service due to a court battle by his opponent’s camp, he then won a special election unopposed in 2015, in Hillsborough and Pinellas counties, meaning that he was in a unique position: He had four years of experience in the House and now was starting over. He could, therefore, potentially serve four more terms, and, like Renner, he was now a redshirt freshman of the Class of 2016.

A story in the Tampa Bay Times indicated that Grant was a likely frontrunner for speaker because “those who have been in Tallahassee the longest often have the edge.”

“It was definitely bold reform. At the end of the day, he ended up winning the argument. … It got people’s attention.”

—TRAVIS HUTSON, former House member and current Senate member, on Renner’s fight in 2017

Moreover, because of his prior service, Grant had developed a close friendship with Speaker Corcoran, who made all the committee chair assignments. Because of his prior service and experience, it would be natural for Grant to be given a prominent assignment in the 2016 session.

Grant recalled meeting with Corcoran before the 2016 session, and they discussed the possibility of Grant running for speaker. After such a tumultuous campaign in Sprowls’ class and the rule change that followed, Grant said he was told that it wouldn’t be fair for Grant to be given a key committee assignment and also run for speaker; he’d have to choose.

Grant recalled: “I really deliberated for a while on whether or not I really wanted to do it [campaign to become speaker], because I’ve seen the job up close, and the job is lonely. It’s really hard. When you see the realities of it, it’s kind of sobering.”

But in the end, Grant decided he wanted to be speaker. He would be treated like all the other freshman, and he would aim to be their leader in 2022-2024.

The competition was set, and Grant was the favorite.

Corcoran saw four who had a legitimate shot at becoming speaker in the new system, including Grant and Renner. Looking back, Corcoran reflected that if the old rules had still been in place, “Paul was not in first place.”

Grant is a man with a big personality; Renner, by comparison, is quiet and methodical.

Speaker Corcoran and the leadership team convened to decide what the House’s priorities would be for that session, in 2017. Knowing that this could be the time for each of the 2022 speaker candidates to prove themselves to their classmates, Corcoran told his leadership team, “We don’t want to play favorites. Let’s get all four front runners and give them each a big, hairy, audacious goal that we want to pass.”

Grant was asked to sponsor the Assignment of Benefits bill. It was a complicated bill pitting the House against powerful special interests in the insurance industry. But as Grant called it, it was a “kitchen table” bill, meaning it was something that directly impacted family finances.

Renner was given an even more difficult assignment, a bill that would challenge the effectiveness of two entities in the state’s economic development arsenal: Visit Florida and Enterprise Florida. With this bill, Renner would not just be confronting the state’s tourism industry and the local economic development officials who benefited from state involvement in attracting businesses to their cities. He would also be confronting the most powerful politician in the state: then-Gov. Rick Scott.

Scott ran his Republican campaign on one thing: jobs. Anything that threatened to chase away tourism jobs or that would allow jobs to be lured to neighboring states was going to evoke Scott’s most passionate response. Whatever political capital he had, Scott was ready to spend it to defend jobs.

Renner took the bill from Corcoran and read it. Then he started doing his research. He talked to leaders all across the state to try to understand the issue. He sought out case studies to determine whether taxpayer dollars were being spent wisely on promoting tourism and corporate incentives.

He recalls amassing thick binders of information and studying the issue leading up to watching the Super Bowl.

And his conclusion about corporate incentives?

“What I saw was a huge difference between what was promised at a ribbon cutting and what actually happened in practice,” he said.

What he learned was that those who most supported the state giving money away were those who were receiving it. “But,” he recalled in a recent interview, “it was not at all in the best interest of taxpayers that their money would be spent enriching companies — maybe Fortune 500 companies — to come into Florida and compete against our local businesses.”

The state also was spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise its attractions to out-of-state tourists.

“The question there is really whether Florida is a secret, so much so that we need to spend $75 million a year to advertise the state to others,” he said.

Should the state spend those dollars at the expense of other priorities, such as teacher salaries or the Florida wildlife corridor?

“Virtually no one on either side of the aisle, Democrat or Republican, will list those two appropriations [Visit Florida and Enterprise Florida] as their No. 1 appropriation, or the No. 1 priority of the state, and for the most part, it wouldn’t be anywhere in the top five,” Renner said.

If spending money to advertise Florida wouldn’t be any individual area’s top priority, then why would the state, which is required by law to balance its budget, spend money on it?

The more he read and discussed the issue, the more passionate he became.

“I discovered that the lack of great case studies in defense of corporate welfare was simply because there weren’t any,” he said.

Visit Florida and Enterprise Florida needed to be eliminated or reformed significantly.

As expected, Scott pushed back.

In an interview with the Florida Channel, he accused those who supported the House bill, which was sponsored by Renner, of being job killers.

“The Florida House — they don’t care about people’s jobs,” Scott said. “These are individuals who haven’t experienced what I went through as a child; have never been in business; don’t know the difficulty of building a business; must not think about the importance of business or jobs; are not thinking about their constituents. ... They are individuals who have never been in business, and they want to lecture me.”

As Scott toured the state, he encouraged citizens to contact their representatives in the House — including Renner — and tell them to oppose the bill and to save jobs.

Corcoran recalls it being a battle. “It went from 70 degrees to 2,000 degrees overnight,” he said. “And there’s Paul at the front of the spear, leading the charge.”

Of the four assignments given to the four frontrunners for speaker, Corcoran said, Renner’s not only turned out to be the hardest, but also the most publicized — and “it was the most troubling to the membership.” In other words, House members themselves often sympathized with Scott’s message and needed reassurance.

“He had a very well-thought-out position on this. This is what he felt. He wasn’t just grandstanding.”

—MILISSA HOLLAND, on Paul Renner’s approach in 2017

Politically, Corcoran said, it was like Renner being on a damaged Apollo 13 and being asked to make it work.

Sprowls, who was speaker of the Class of 2020, recalls the battle with Scott as Renner’s “make or break moment.”

It was a political opportunity of a lifetime to have such a publicized bill—one that dominated the session from start to finish. “But you had to do well, and so it was risky,” Sprowls said. “It was high profile, and therefore success or failure would be high profile. But I think he knew that he could do the work.”

In Corcoran’s judgment, Renner did the work.

When other members of the House called him to ask why Renner felt he was right and Scott was wrong, Renner patiently explained his position.

The battle was “constant,” Corcoran said, and the consequences of the bill were tremendous. House members were being asked to vote for something that philosophically aligned with what they stood for — limited government and free markets — but that could mean some businesses, including donors, who were used to getting state money would be upset.

Renner, Corcoran said, “held the troops together and made sure they understood the vision.”

Locally, Renner also faced opposition, with the Flagler County Chamber of Commerce president and the Flagler County Economic Development director, who sided with Scott and urged residents to tell Renner to save local jobs. Milissa Holland was the mayor of Palm Coast at the time, and she recalls being troubled by the House bill. But she was among those who met with Renner, heard his stance, and came to agree with him, despite any possible adverse impacts locally.

“He had a very well-thought-out position on this, and he articulated it very well, and he stood strongly in his position,” Holland said. “This is what he felt. He wasn’t just grandstanding.”

She remembers Renner speaking on the radio about the issue several times. He also wrote an op-ed in the Palm Coast Observer to make his case.

On the House floor, many asked Renner tough questions, and Renner had answers for everything.

As with any bill, legislators ask question to “expose weaknesses in the legislation or expose the bill sponsor as someone who doesn’t understand the impact of the legislation,” recalled another House leader, Ray Rodrigues. “Nobody was able to do that with Paul. Paul had clearly thought through the implications … He was able to demonstrate a mastery of the issue and just as importantly, why that policy was the right public policy that we should pursue. So I think he showed courage as a freshman, carrying a bill that was not popular with the executive branch. And he showed his mettle that he was prepared, ready to defend the policy and advance it.”

With some compromises achieved, Visit Florida and Enterprise Florida were reformed, with more accountability required, and Scott signed the bill.

Travis Hutson, who represents Palm Coast in the Florida Senate, recalled watching Renner in action. It wasn’t surprising to him that he stood firm in his convictions. From the first time he met Renner, Hutson believed he had “the ‘it’ factor.” He was thoughtful, centered, principled.

“It was definitely bold reform,” Hutson recalled about the Visit Florida fight. “At the end of the day, he ended up winning the argument. … It got people’s attention.”

After the session ended, the candidates for speaker had about two months to campaign to the other two dozen of their 2016 classmates. Four candidates — including James Grant and Renner — delivered speeches in the conference room of a hotel in Orlando in June 30, 2017. The top two, assuming no one earned more than 50% of the vote, would go to a runoff.

The way Grant remembers it, he and Renner were philosophically aligned almost perfectly. One of the ways he differentiated himself was to show that he was uniquely suited to help improve Florida governments’ technological efficiency and cyber security. He told the members that this was a defining moment, when they had a chance to make a difference in how Florida was positioned for the future.

Rodrigues, a House official who was asked to help preside over the organizational meeting that day, recalled the impact of Renner’s speech.

“What I remember was, he was asking for their vote and that the agenda that they would pursue would be an agenda that would be decided together,” Rodrigues recalled. “And I know that that concept connected with his class. They were very interested in a leader that was listening to them and engaging with them and working with them. … He was very deliberate about saying, ‘I’m not asking you to vote for me so that I can lead you. I’m asking for your vote so that we can go together.’”

Rodrigues helped tally the secret ballots outside the conference room, and the meeting reconvened. He then announced, “There will not be a runoff. A candidate has secured a majority on the first ballot, and that candidate is Paul Renner.”

Renner had defeated his rival, Jamie Grant, and could have attempted to minimize Grant’s influence and grow his own.

He did the opposite.

According to Grant, Renner fulfilled his promises to work together for the benefit of the state. Before the speaker election, Renner and Grant became friends and met at a popular place in Tallahassee called Bird’s Aphrodisiac Oyster Shack. There, they committed to each other that they would not let their competition for speaker damage the legislative success of the House, as had happened in the past.

Grant recalled: “We looked at each other and said, ‘Look, this dynamic has to change. We are one team.’ I look at it like spring quarterbacks: You’ve got two guys that want to be a quarterback in the fall, and it’s a really intense competition. But in the fall, we wear the same jersey.”

In the next session, Renner was appointed to be the chairman of the powerful Judiciary Committee, which has two subcommittees, Criminal Justice and Civil Justice.

“And while the speaker is going to make all the appointments, the speaker at that time was very deferential to who you want,” Grant recalled. “Paul was adamant that I be his Criminal Justice chairman. So we’ve just gotten out of this race, and the first thing he does is say, ‘Hey, I want you on my team, because we’ve got this really big agenda in Criminal Justice.’

“I think a lot of other people were shocked because typically, when that race is over, the loser’s kind of bitter and whining and figuring out, ‘OK, what I do next, and how do I recover?’ and the winner’s kind of gloating. … The first thing Paul does is honor everything we’d been talking about.”

That year, Renner, Grant and the rest of the legislators tackled the implementation of three controversial Constitutional amendments: restoration of felons’ rights, Marsy’s law, and the reformation of the Constitutional amendment process.

“None of that happens if you don’t have a chairman like Paul,” Grant said. “We took on probably three, four, five terms’ worth of work together. ... He welcomed me with open arms, and we did a lot of great work as a result.”

Today, Grant is no longer in the House; in 2020, Gov. Ron DeSantis asked him to be the chief information officer of the state’s beleaguered Division of State Technology, to help turn it around and do exactly what he had campaigned to do in his attempt to become speaker.

“Now he’s the speaker, and I’m running state technology,” Grant said with a laugh. “I think it worked out the way it should.”

Renner’s attitude about treating others well extends beyond those in power, according to Darrell Boyer. Boyer was a student at Florida State University and got a job in Tallahassee during one of the legislative sessions. He met Renner in an elevator once.

“He took the time to ask me my name, ask me what I was doing in The Capitol,” Boyer recalled. “He said, ‘God bless, and have a great day.’”

Renner was chairman of the Rules Committee at the time, an extremely busy position, and Boyer said his own position would be considered “the bottom of the barrel.”

Boyer was inspired. When he learned that Renner was going to be a guest speaker at a Tiger Bay meeting in Flagler County, he drove three hours to listen. Afterward, he introduced himself again, and Renner ended up offering him a job.

“As a poor college student, I was actually very scared,” Boyer recalled in an interview in the summer of 2022. “I didn’t have a job lined up.”

Boyer became an aide to Renner, and he said he has seen the same pattern continue: “He’s nice to every single person he comes in contact with. … He listens. He wants to do a better job of representing us.”

Even before Renner was elected as speaker, he had been an advocate for one of the biggest state-sponsored wins that Palm Coast has secured, and that is the creation of MedNexus.

“It was high profile, and therefore success or failure would be high profile. But I think he knew that he could do the work.”

—CHRIS SPROWLS, former House speaker, on watching Paul Renner handle the political battle of 2017

Within months of being elected mayor of Palm Coast, Holland met with Renner to share research she had done that indicated it might be possible to attract the University of North Florida to Palm Coast. Renner supported the idea, and he arranged meetings with all the key players in the state who could help make the vision a reality, including leaders in the Board of Governors and two successive presidents at UNF.

As Holland recalls, “That led to the Board of Governors going through a series of approvals before it was heard and approved by the House, the Senate and then ultimately signed by the governor. This was an arduous process. And it was unheard of to be able to complete acquiring and attracting a university to a community within that time period. Normally, it takes five to six years. And I really, truly believe that it’s the evidence of Paul’s leadership and his dedication to this community, to this region. … There was not a step in this process that Paul Renner was not part of this conversation.”

That effort also involved Hutson, but he gives the credit to Renner and Holland. MedNexus is one example that shows Renner’s skills as a legislator. Hutson said: “He’s the kind of guy that can get it done.”

In another instance that could have gone differently with someone else leading the class, Hutson explained that an environmental bill he was promoting in the Senate raised a concern from a new House member in the Florida Keys. Renner listened to the representative and arranged a meeting with Hutson to make sure that all sides were considered.

Hutson remembers the conversation like this: “Paul Renner said, ‘Look, you may be right, Senator Hutson, but this affects one of my members. Sit down and talk to him. Let’s see if we can find common ground.’ Those are the type of characteristics that prove that he is a great leader for all of his colleagues.”

As with MedNexus, Renner deflected any credit for helping to resolve the concerns on Hutson’s bill. He said he sees his Republican members as a family.

“If there’s an issue that is of significance and significant importance to one of our members, then it’s important to me,” he said.

One of the most significant bills Renner was involved in in the most recent session was the Parental Rights in Education Bill, one that many around the nation saw as emblematic of ideological warfare. Was this bill a political tool by the right to energize the base, or was it something Renner actually believed in?

Renner acknowledged in a previous interview that some have called him ideological, and he rejects that label. He said one of his strongest motivations as a legislator is to strengthen families.

In Sept. 21, 2021, he delivered a speech to the Florida House, when he was honored for his role at the time as speaker designate. He said, “If every child grew up in a supportive family, most of society’s problems would disappear.” Moreover, “if strong families disappear, our society would crumble and no amount of government programs could save us.”

In addition to his own strong family as a child and teenager — his father was a minister and his mother was a public school teacher — he also had one experience as a prosecutor in the late 1990s that reinforced his ideas on the importance of fathers in society.

“I always tell people if they haven’t met Paul, he’s just a super honorable Eagle Scout kind of guy. His word’s his word.”

—RICHARD CORCORAN, former speaker of the House

In Broward County, he went through a leadership program, which included a visit to a prison where 200 juveniles were being held. Their crimes were serious enough that, if convicted, they would be sent to prison with adults. An inmate — a teenager — gave the leadership group a tour, and Renner pulled the teen aside and asked, “How many kids here have a relationship with their father?”

“Two,” the teen said. “Me and one other kid.”

During my interview with Renner in the conference room at Flagler Broadcasting, at this point, the interview came to a pause as Renner tried to collect himself. With tears coming to his eyes, he said, “Don’t tell me that fathers don’t matter.”

“What did you think when you heard him say that?” I asked.

“Sad,” he said.

“Did you think about your own father?”

Renner didn’t answer the question directly. Apparently still lost in that memory, he just repeated: “Sad.”

When he composed himself, he apologized for getting emotional and then joked that his own fatherhood was likely to blame. He has a toddler and an infant at home.

“I’m getting three or four hours of sleep a night,” he said. “I didn’t mean to break down on you. But fathers matter a lot. So that’s why I get up in arms about this whole parental rights bill.”

He was referring to the bill that gives parents more control over what their children are taught at school. It also ensures that homosexuality and gender identity cannot be discussed before fourth grade, and only in an “age-appropriate” manner after that. Opponents called it the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, a term that Renner despises; he feels it’s a gross manipulation of the bill.

“Look,” he said during our interview, “you can raise your kids the way you’re going to raise them. And your faith and your values – I’m 100% behind you, even if they’re different from mine. But that isn’t the role of the schools. Their job is to teach kids to read and do math.”

There is an “elitist view” that typically comes from the political left, he said, that says, “‘We know best. We know better than parents how to raise your children.’ And I find that really offensive, and I’m 100% committed, in opposition, to that philosophy.”

He continued: “If you want to teach your kid to be a progressive Democrat, to believe there’s no God, to think that our country is a terrible, awful place, then I support your right to do that. That’s your family. Those are your values, and you’re entitled to them as an American. Period.” For emphasis, he repeated: “Period. This idea that we’re going to try to cancel people, or take kids and indoctrinate them against what their families believe, is the end of America. We need to do everything possible to strengthen families.”

Renner said strong families are among the most important tools to battle drug abuse, mental health struggles — just about every societal ill.

To weaken the family is akin to attempting to “reject human nature.” It’s a philosophy that would “reject the world for what it is, for the world that they want. And that is ideology. And that’s why I say that I don’t see myself as an ideologue.”

He doesn’t see himself simply as a conservative but first and foremost as someone who loves the Constitution. But, he added, “I hope that’s everybody.”

After the organizational meeting on Tuesday, Nov. 22, Renner will serve as speaker of the House until his final term comes to an end, in 2024