- April 8, 2025

Your free article limit has been reached this month.

Subscribe now for unlimited digital access to our award-winning local news.

From the time it was proposed in 1960, Tomoka Oaks was marketed as a community surrounding an 18-hole golf course.

And it was, for almost six decades.

It was still operating when Carolyn Davis and her husband purchased their home in the subdivision in 2014. She remembers entering the clubhouse one day, just to see what it was like.

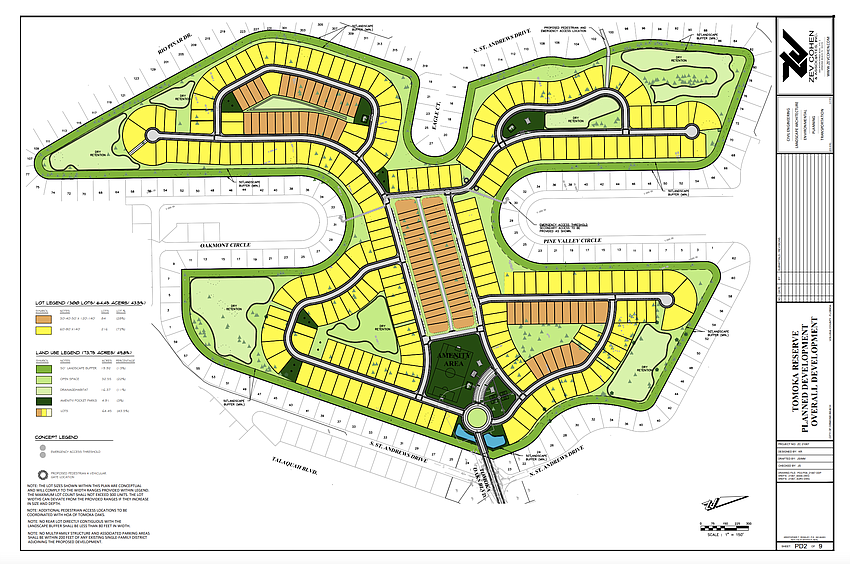

Now, nine years later, Davis is among the number of residents within Tomoka Oaks, particularly those whose properties abut the golf course, that wish to see the land remain as it is. The looming alternative? The construction of 300 homes.

In a meeting with the Observer in November 2022, as she sat in her dining room — the walls of which are covered with white sheets of paper detailing the timeline of ownership for both the subdivision and the golf course — Davis questioned whether the golf course could legally be developed, as she believed an original covenant of the property that declared it be used perpetually as a golf course remained valid. She still does.

“What was the original intent of this development?” Davis asked. “How many people invested in the development based on the master plan? Just because something was filed 30 years ago that negated restrictions, does that make it right?”

But the city, developer and the voluntary Tomoka Oaks Homeowners Association believe the covenant is void.

Local developers Carl Velie, Ray Barshay, Sheldon and Emily Rubin purchased the 147-acre golf course property in April 2021, three years after the golf course closed. From the beginning, they indicated they wanted to build single-family homes.

For Velie, it was the location and “excellent development conditions” that first called his attention.

“Most sites available today are low and require a substantial amount of fill,” Velie said in a statement to the Observer. “As such, your end product lacks the rolling nature that can be built into this development. My vision is to provide residents who live or want to live in Ormond Beach a beautiful new neighborhood where they can reside within an efficient, modernly designed home.”

As a local developer who has lived in Ormond Beach since 1963, and with a family heritage that dates further back — his mom was raised in the city as well — he is more concerned with developing a subdivision he feels would be an asset to the community, while still being an economically-viable development.

The developers have taken into consideration the concerns expressed by residents at the Feb. 8 neighborhood meetings, Velie said. They have since made changes to their plans, such as reducing the number of lots and arranging the development so the larger lots are around the perimeter of the development. They are also investigating if any improvements can be made to the diamond intersection at Tomoka Oaks Boulevard and North and South Saint Andrews Drive.

“The ownership group and the rest of our development team members are constantly analyzing to see how to make the development more in tune with the residents’ desires,” he said.

Tomoka Oaks’ origins date back to 1960, when the 545-acre development was approved by the Volusia County Commission at the time.

It wasn’t a smooth road. The city of Ormond Beach was in the process of annexing about 4,500 acres of land into its city limits, including the Tomoka Oaks property, and according to reports by the Daytona Beach Morning Journal, the annexation was hit with eight lawsuits in opposition, all of which were ultimately dismissed by a circuit judge.

Construction for both the subdivision and the golf course, initially known as the Sam Snead Golf and Country Club, began in 1961, and for the next 18 years, the properties saw several different owners, including William McElroy, Ralph Frederick and Milton Pepper.

Davis is not a lawyer, but she’s always loved history, so when attending a meeting by the HOA’s golf course committee regarding the development of the golf course following its sale in 2021, her interest was piqued when her husband asked if there was a possibility that past conflicts of interest could prevent development. He was told the “records didn’t go that far back,” Davis said.

She made it her project to find those records, and for the next year, looked up any references to Tomoka Oaks and its golf course in newspaper archives, went through old deeds and crafted a record of everything she found.

“The more I looked into this, and when I found this deed that said it’s to be perpetually a golf course ... that to me was like, ‘Wait a second, the records do go that far back,’” Davis said. “I want to see where this leads.”

Tomoka Oaks and the golf course, she said, were designed to coexist for mutual benefit. It’s her opinion that people like Milton and Frederick had a conflict of interest in cross-ownership when filing and making modifications to the protective covenants and restrictions of the golf course .

She compiled her research and has since posted it onto her website, TomokaOakshistory.com. She has also started a monthly newsletter.

“There are other Tomoka Oaks residents who I am in contact with constantly, who also are interested in exploring every avenue for stopping development,” Davis said. “The homeowners association has put their resources into how to get the best new development possible — how to represent the existing owners’ best interest. They are aware of the research. They have chosen not to associate themselves with it.”

Helping the HOA advocate for mitigating the impact of the proposed development of the golf course keeps Jim Rose busy in retirement. A former real estate law attorney, he’s reviewed the documents. He’s consulted with the HOA’s legal representation, local land use attorney Dennis Bayer, and gotten an opinion from the city’s attorneys.

If Davis believes there is a covenant to prevent the development, she needs an attorney to back up her opinion, said Rose, who is the chair of the HOA’s golf course committee.

“The problem I have is that, as long as people think that there’s perhaps a covenant or some kind of way to stop the whole thing, it’s hard to get a consensus together,” Rose said. “It’s understandable. These are people’s’ homes. It’s a big deal. It’s my home — if I could find a covenant, I certainly would to say, ‘You can’t do that stuff.’”

He lives along the golf course, too. Rose moved to Tomoka Oaks in 1990 because, as a golfer, he wanted to live on a course.

Here’s what the city’s assistant Attorney Scott McKee stated in a June 30, 2022 email regarding the covenant: Yes, it existed, but a 1963 warranty deed also noted a reverter clause where the condition that the golf course be used as such in perpetuity could be released under a two-thirds vote after 10 years by the Tomoka Oaks board of directors.

A meeting was then held in 1969 after the Tomoka Oaks property was sold to Frederick and a sale of the golf course was pending to Ormond Ocean Homes, Inc. At this meeting, the board of directors voted released the covenant, to become effective in 1973.

“In summary, the records confirm the existence of a document recorded in the public records that provided the property be used for purposes of a golf course in perpetuity,” McKee wrote. “In this case, the document was not contained in covenants and restrictions provided by a homeowners’ association, but rather in a warranty deed, and as stated previously, subsequent records confirm the reverter clause containing the language was properly released by a recorded corporate resolution and release, and therefore no longer valid.”

Davis has seen this email before. In an email, she stated that she believes the city “did not perform thorough due diligence when they disregarded all the research related to conflicts of interest in cross ownership which place a question on the release of the covenants and restrictions intended to protect homeowners.”

“The city is certainly entitled to their opinion, just as I am,” she said. “But the only opinion that matters is a judge's opinion."

The current development proposal for the golf course is not the first for the property.

First came the Tomoka Oaks Golf Village proposal.

In 2006, the Ormond Beach City Commission approved Dr. Richard Ryals’ proposal to build 35 townhomes and six condo buildings on about 30 acres of the property. According to the Daytona Beach News-Journal, his proposal also included a new golf clubhouse and changes to the golf course.

Ryals’ proposal, which included a rezoning of the property to Planned Residential Development, expired in 2014.

In meeting with the Observer in December 2022, joined by Davis and resident John Anthony, who has since died, Ryals detailed why his development never occurred. For one, the financial crash happened soon after his development was approved. He had also ran into water issues with the city and St. Johns River Water Management District in previous years.

Ryals, who bought the property in 1979 and operated the golf course for the next 31 years until he sold it to Putnam State Bank, said residents who believed the golf course was forever restricted to that use were misinformed. In fact, he said, the lack of a restriction was why he — a resident of Tomoka Oaks himself — held onto the property for so long.

“I was afraid some unscrupulous developer would come in and start building homes back there, which is exactly what’s happening,” he said.

He counseled Davis and Anthony to find legal authority to determine if the covenant is still legally binding. But he also didn’t agree with the HOA’s mission to focus on mitigating the impacts of the development rather than finding a way to halt it.

“That’s admitting defeat,” Ryals said.

The Tomoka Oaks community hasn’t changed much since Rose moved in. The number of kids has ebbed and flowed, and people have moved in and out, but the biggest change has been seeing the golf course go downhill.

“It’s a big change when you’re used to having the beautiful vistas and such, and now all of the sudden, [development] impacts the value of your home and impacts your enjoyment of it,” he said. “So that’s going to be a big change for folks.”

The HOA has met with the developers around seven times. Rose understands that as a voluntary HOA with only about 60% of residents as members, the HOA can’t singlehandedly steer the ship.

“When you’re dealing with decision-makers, they want to see a consensus, which is what we’re trying to do, and a position so that we can negotiate,” Rose said. “... The greater the mass, the more impact you have when you’re negotiating or when you’re advocating a position.”

From Velie’s perspective, his group’s proposal would make better use of existing infrastructure and services, and has the potential to bring new life to older neighborhoods.

“It can create new places to live and work and support local businesses,” he said. “Infill development is critical to smart growth policies.”

One misconception some may have, he said, is that smaller lots mean cheap homes. The reality, he said, is that economic conditions and homebuyers’ desires have changed since Tomoka Oaks was developed.

“Today, a large lot is 75 to 80 feet wide, not 100 feet,” he said. “In many of the new developments, you have homes on these size lots sell in the $650,000-$700,000 range. Increasing the lot sizes to 100 foot wide will result in [raising] the overall price of the home to $1 million or more, which puts it out of reach for many of Ormond Beach’s residents.”

In a phone conversation a couple of weeks after the Feb. 8 neighborhood meeting, Davis’ opinion didn’t waver. The neighborhood meeting felt like a formality, she said.

“There was no real effort made to make this a presentable development that the community would want,” she said.

She understands the city’s stance that the golf course is free to be developed. She continues to respectfully disagree. In the March edition of her newsletter, she remarked on the collective desire she saw at the meeting of residents wishing to prevent the golf course’s development. She signed her message, “Not giving in or up.”

When the Observer asked what keeps her going, she said she is finding that her desire to educate her neighbors and protect Tomoka Oaks’ characters “comes from something larger than myself.”

“The more I talk to people, the more convinced I am that we have something special here in Tomoka Oaks, and my motivation comes from knowing that what I am doing could have a lasting, positive impact on our neighborhood and all of Ormond Beach,” Davis said. “That is what keeps me going.”

Your free article limit has been reached this month.

Subscribe now for unlimited digital access to our award-winning local news.