-

-

Loading

Loading

In that early, jump-scare stage, I would cringe every time we drove by a mailbox.

My son, Grant, taught me how to drive.

“You have to hold down the R button to drift,” he said to me about a year ago, as we played Mario Kart on the Nintendo Switch.

“I’m doing that, but it’s still not working,” I said, a note of middle-aged exasperation in my voice.

He responded patiently: “You have to hold it down the whole time you want to drift.”

I remember the good old days, when the kids were smaller and we raced the easiest level: the oval track. Sure there were a few banana peels on the pavement, but nothing I couldn’t handle, and no need to drift. Now, as my children have gotten older and more capable, and the games more advanced, I was being subjected to horrible tracks like Rainbow Road, which is like riding a bucking bronco in space.

“This is dumb,” I said, as I was struck by a spinning turtle shell of shame and fell off the track once again, ensuring my last-place finish.

I got my revenge, though, on the real road, because around that time, Grant got his learner’s permit.

“Stop,” I said one morning, as he rolled into the roundabout at U.S. 1 and Matanzas Woods Parkway just in front of a truck. “Stop,” I said again. “STOP!”

“I was stopping,” he said.

“No, no, no, no, no,” I said. “You have to stop EXACTLY when I say so.”

“I thought I had room.”

Other times, in that early, jump-scare stage, I would cringe every time we drove by a mailbox.

“Wait!” I would say as Grant pulled into our driveway too close to the edge of the concrete, the wheels of the car seemingly dangling over the edge of the culvert pipe.

As the weeks went by, and Grant dutifully tracked his driving all the way up to the requisite 50 hours, he got better and better. I stopped feeling nervous and instead felt confident that he would be safe when the time came that he would get his license.

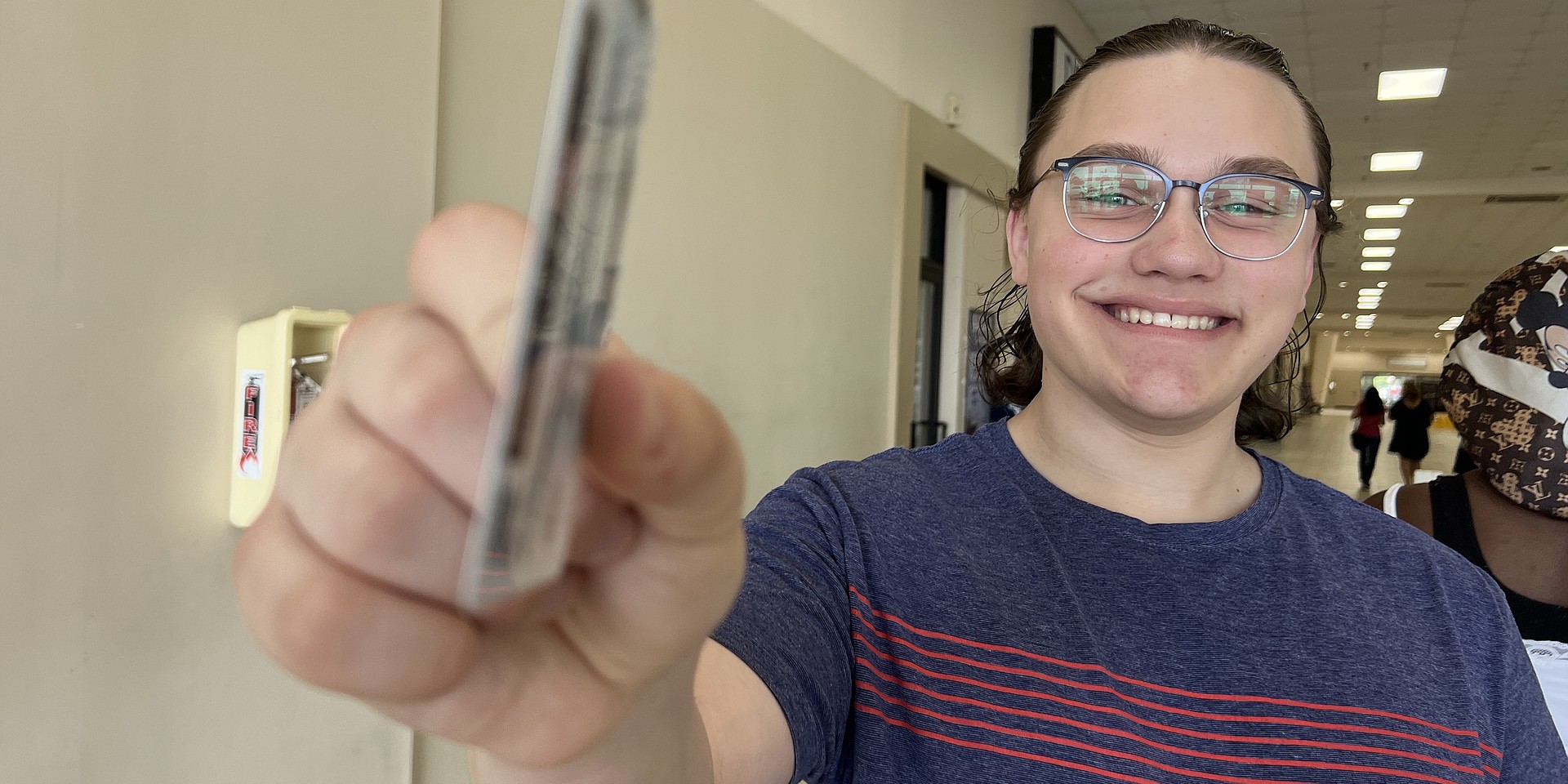

The day of his test finally arrived, and we drove together to the Department of Motor Vehicles. He passed without any trouble, and as we waited in line for his photo to be taken, I took a long look at him: He was still 16 years old, anxious to be an adult and, in most important ways, already as capable and mature as any adult. He would soon be in the club of licensed drivers, the same club of which I was a member, my equal.

I realized that my time with Grant is limited. Two days after he got his license, he turned 17. This will be his senior year in high school. Possibly, we will live under the same roof only 400 or so more nights, before he drives away to his next rites of passage.

As I reflect on that morning in the roundabout, when I had yelled at him to stop, I felt that I was justified in my desire to convey urgency — mistakes as a driver can be deadly. Still, perhaps I can learn something from the patience he showed me when I was trying to learn how to drift. Perhaps I can be less competitive and more supportive.

The other night, as a family activity, we played Mario Kart again, and I have to say, I am actually a good drifter now, deftly scooting around curves, getting that bonus boost just about every time I aim for it. I even finish in first place every so often, eliciting looks of mock amazement from my children.

I found myself looking up from the couch at Grant that night, to comment on the amusing irony of how Grant had taught me to drive a Mario Kart at the same time that I had taught Grant to drive a real car. But he wasn’t home. He was out with friends, driving solo.